People warned us not to go to Cairo. But we did anyways. And yes, we found destruction and decay. But we also found hope. Hope from the people desperately trying to preserve their town and its history.

This post has taken a while to write, because we haven’t been able to stop thinking and talking about Cairo since our visit. We both have an interest in historic preservation. We used to live in an 1840s farmhouse- one of the oldest houses in the county, and were involved in different ways with preservation projects through Josh’s former work. So when we saw that The Cairo Historical Preservation Project (TCHPP) was hosting a free bus tour of Cairo and some of the historic preservation work being done in the city, we knew that was the perfect opportunity to visit Cairo. The tour was one of the pre-event events during the Magnolia Celebration fundraiser (which we would have loved to go to, but was out of our budget). Our tour guide, Tara, was born and raised in Cairo, and it added so much to the tour to be able to hear her stories of growing up there.

Tour of Cairo, Illinois

Cotter Field

Our first stop was what was once called Cotter Field, which from 1943-1945 was used by the St. Louis Cardinals as their spring training camp. They had to stop using the site after only 3 seasons because of it flooding. There are still a lot of Cardinals fans in Cairo. Actually, we found a lot of Cardinals fans all over southern Illinois, which felt very strange to us Cubs fans from the north. Besides the Cardinals, Cairo used to be a very active minor league baseball city too.

Cairo’s Civil War Contraband Camp

Our next stop was an empty field that had recently been recognized by the National Park Service. To really appreciate the significance here, you’ll need to close your eyes and imagine yourself back in the 1860s. This field was then part of Camp Defiance, a Union Army camp. It was what was called a “contraband camp” at the time, which meant it housed escaped slaves. Since Cairo is right across the river from the South, it makes sense that it would be the first destination for many escaped and newly freed slaves- especially after the Emancipation Proclamation. In recent years, researchers from SIU along with the TCHPP have been doing work on researching the contraband camp site and working on a National Register nomination. In April this year the National Park Service designated this site as part of the Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. They plan to eventually add interpretive signs to the site to tell its story.

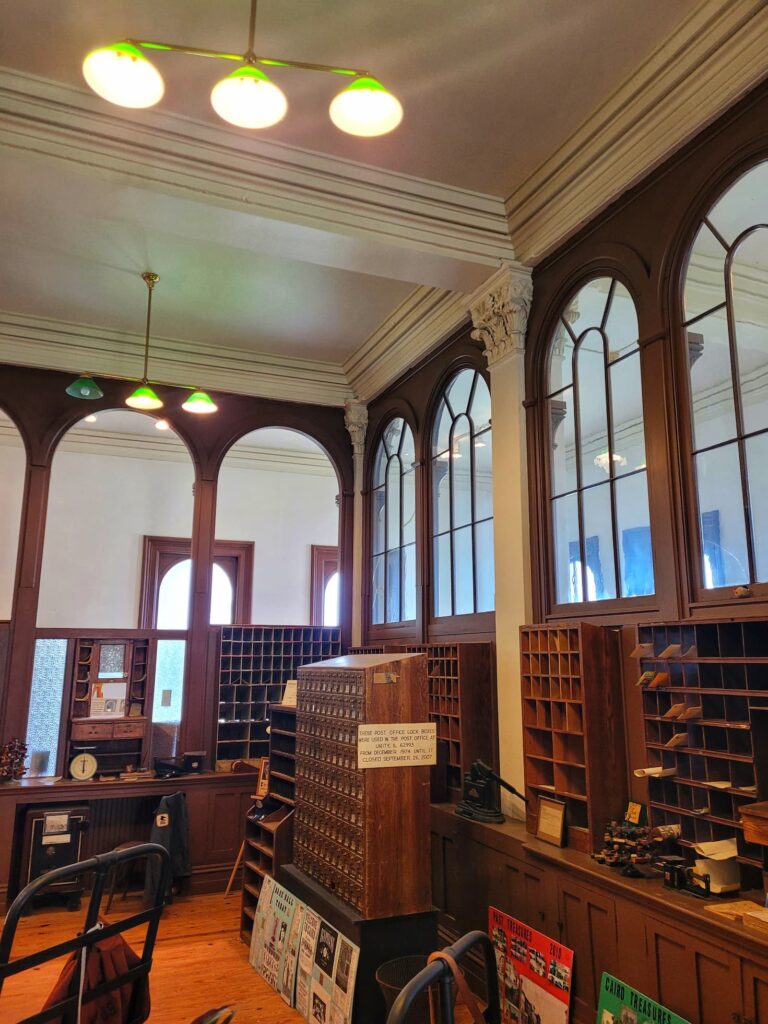

Cairo Custom House Museum

We were very excited that the Custom House was open for this event, because it’s usually closed. They used to offer limited, but regular hours, but now you can only visit if you’re lucky to catch them during an event or can call and schedule with someone. The volunteer working the day we visited told us that she was the only volunteer docent left.

The Cairo Custom House was built over 1869-1872. It was a federal customs house, post office, and court house. Back when the Custom House was built, Cairo was a thriving steamboat town, which is why the federal government decided to build a customs house there. It’s one of very few surviving custom houses in the US and one of the largest federal buildings from that era in the region. In 1973 the Custom House was added to the National Register of Historic Places, but it needs massive amounts of work to survive. The third floor, which houses the federal courtrooms, has so much damage that it is closed to visitors. When we ventured to the second floor, there were rooms and sections of hallway blocked off because of damage as well.

The first floor of the museum is mainly one large room with displays scattered around. There’s artifacts and information about local history, the Civil War, steamboats and river history, Lewis & Clark and the Corps of Discovery. The second floor is smaller rooms off a main hallway, each with a different theme such as a general store or doctor’s office.

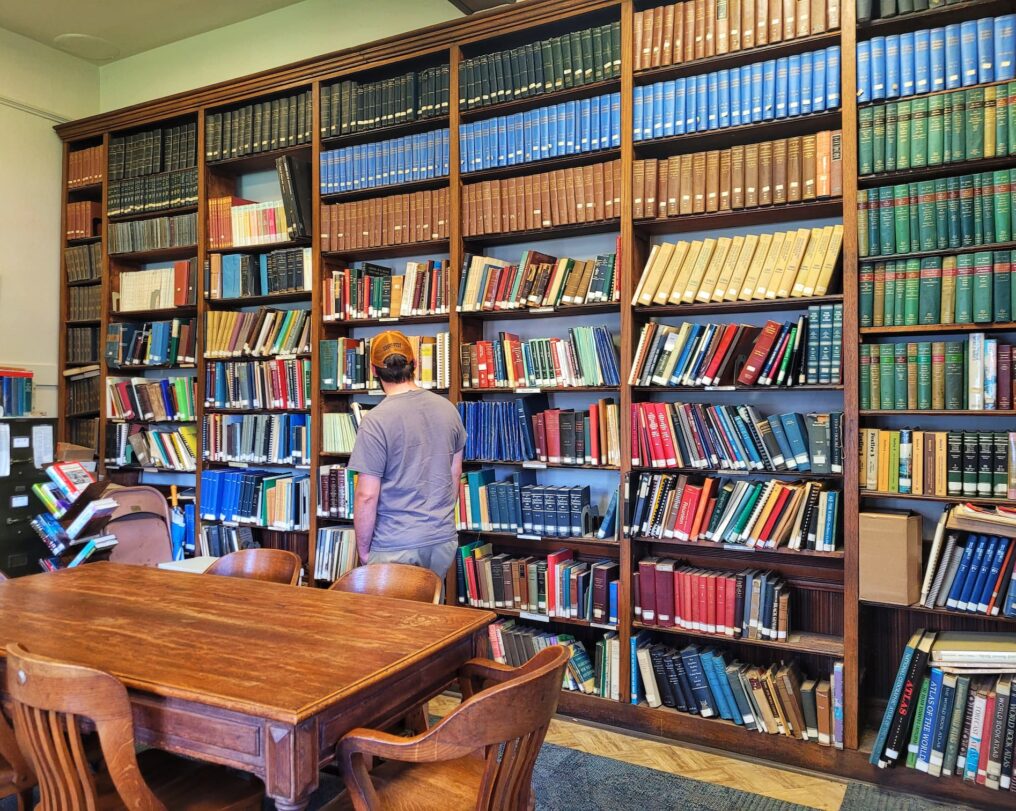

A.B. Safford Memorial Library

Cairo’s public library is housed in the A.B. Safford Memorial Building. This building was donated to the city by Anna Eliza Safford after her husband died. The library receives some funds from the city, but is largely supported by public donations. After all its years of being in service, the library is only on its 7th librarian. Besides the usual stacks, there are several research and meeting rooms, as well as display cases and small exhibits around the museum. While exploring upstairs, we also saw Cario’s other presidential desk, which is on permanent loan to the library from a former Mayor. Supposedly Andrew Jackson used this desk at the Bank of the United States in Philadelphia.

Ward Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church

Next, we stopped in front of the Ward Chapel A.M.E, but because of extensive damage to the building, we were unable to go inside. The Ward Chapel was organized in 1863 and dedicated in 1875. There isn’t good documentation, but the church is thought to have been a station on the Underground Railroad. Then, in 1916, there was a fire in the church basement, but members were able to rebuild by 1918. The pipe organ purchased by the congregation in 1929 is still inside. In the 1960s the A.M.E. saw some famous visitors during times of racial tension in Cairo (and across the nation). John Lewis held training sessions in the basement and Revered Jesse Jackson visited to speak to the congregation.

Although the Ward Chapel is so damaged that’s unusable, it is a ray of hope in the community. Earlier this year the church was a recipient of the National Trust’s Preserving Black Churches grant, part of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund. The Fund has given over $4 million to protect the legacy of America’s Black churches. The Ward Chapel was included in the second round of funding, and was one of 31 recipients in that round. The grant is a planning grant- which means the money is going into surveying and developing plans for preservation, but not for actual construction. Plans so far include restoring the existing masonry of the entrance and bell tower, and of course stabilizing the building. There are also plans for adding an addition to the back of the building that would be used for a museum and meeting space.

First Presbyterian Church

The First Presbyterian Church was built in 1855 and is located right in downtown Cairo. In 1893, the congregation decided to build a new building in uptown- closer to where many members lived. This building was finished the following year and also included a parsonage. As Cairo’s population shrank, so did the congregation size, and the church began to deteriorate. Today it’s maintained by the Presby Tips Foundation, who is currently trying to raise funds for basic maintenance and eventual rehabilitation. Since there is no longer an active congregation, the Presby is legally considered a church museum, which has increased the real estate taxes on the property.

While I was busy admiring the stained glass, Josh noticed light coming in from spots in the ceiling. This means the building needs stabilization very soon or it isn’t going to survive. During the pre-celebration events for the Magnolia Celebration, several historic churches were holding open houses. I wish we had had time to explore more of them, but I’m glad we got to stop into the Presbyterian as part of the tour.

Magnolia Manor

We didn’t have a chance to actually tour Magnolia Manor, but our tour started and stopped there. The home was built in 1869 but businessman Charles Galigher and is not run as a period house museum. The 14-room house is on the National Register of Historic Places. One of the more interesting parts of its architecture is the double walls that have 10 inch air spaces between them to keep out dampness. Magnolia Manor is considered one of the crown jewels of Cairo, and is a great example of keeping the historic architecture of the city alive.

Misc. Sites Around Cairo

Besides the stops where we got out and explored, we learned more about Cairo from our bus seats as we drove around the town hearing Tara’s stories.

These tunnels, next to the river, have legends about being used for the Underground Railroad. It’s not confirmed, but there are people looking more into it to try to determine if it’s true.

We stopped next to a car wash beside what used to be the city swimming pool. Tara told us the story about how when she was a little girl she took swimming lessons here, until one day the pool closed overnight. She didn’t learn until later in life that it closed because when the owner of the public faced pressure to integrate the pool, he decided instead to close it permanently. And then, just like that, there was no pool in Cairo anymore.

We stopped off along the river, on the outside of the levee. We watched barge traffic traveling along- it’s still a very active area. One idea for helping Cairo is if they had a harbor, they could capitalize on barge traffic and industry.

Even More to see in Cairo

The Cairo Historical Preservation Project also put together a great map of points of interest in Cairo, which can be found on their website here: Cairo Points of Interest Map

Fort Defiance State Park

Our final stop was Fort Defiance State Park, where the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers meet. There, we stood in the confluence of the two rivers in a town that is reckoning with the confluence of its past and future.

Fort Defiance has changed hands a few times between the state and the city of Cairo. It’s rather neglected and forgotten by the state, but people still travel to it because it’s considered one of the great confluences of the world. Fort Defiance is also Illinois’s lowest point of elevation. A few years back we visited Charles Mound, the state’s high point, so now we can say we’ve really seen the highs and lows of Illinois.

What Happened to Cairo, Illinois?

It’s hard to pinpoint which even most impacted Cairo and led to the state of the town today. Could Cairo have survived any singular pitfall? Maybe. But there are so many combined factors that it’s impossible to know. I’ll keep things brief and high-level here, because there’s so much that could be written about what happened to Cairo. If you want to learn more and hear from residents, I highly recommend the documentary Between Two Rivers, which the filmmaker Nick Jordan has hosted on YouTube: click here to watch.

Racial Unrest in Cairo

Cairo has long been thought of as “a Southern town in a Northern state,” but because it was often the first stop for those escaping slavery, and home to a Civil War Contraband Camp, it has always had a higher than average Black population for similar towns. This means that race tensions started early here. An early major incident was the 1909 lynching of Black man William “Froggie” James. The Between Two Rivers documentary goes into much more detail about what happened and I suggest checking that out if you’re interested.

The late 1960s is when the race tensions in Cairo really gained attention, though. Cairo was a hotbed for the Civil Rights movements and encountered years of boycotts and protesting. Like many other towns in the US in “the long hot summer of 1967,” Cairo had days of rioting and protests. These particular incidents started when a young Black soldier home on leave, Robert Hunt, was found hanged in his jail cell. The official story was that it was suicide, but many in the Black community didn’t believe it and instead believed that Hunt had been murdered. This led to 3 days straight of riots and protests, shootouts, firebombings, and National Guard involvement. UMass Amherst has a photo collection with some great photos of the protests online.

Could Cairo have recovered if this was all that happened? It’s possible. The riots in Cairo weren’t unlike those plaguing the country that summer, and plenty of other towns recovered over time. But it wasn’t just a one time thing here. During the early ‘60s, Cairo had an unbelievably high unemployment rate- over twice the national average. Black people especially could not get work in town other than the lowest paying and hardest labor jobs. White store owners staunchly refused to hire Black employees. Groups, such as Cairo’s United Front and NAACP chapter, got together and decided to boycott any store that refused to hire Black people (as well as picket them). This lasted for years years and was a huge factor in the downfall of Cairo’s economy. In the first year alone 11 businesses closed instead of hiring Black employees. Eventually a third of the stores downtown would close.

Cairo’s Economic Decline

Besides the economic decline brought about by the refusal to integrate businesses, several other changes to the landscape brought about economic decline in Cairo. In its early days, Cairo was a thriving and prosperous town because of the steamboat industry, but as that industry declined, so did Cairo. The building of new bridges also affected Cairo. When a bridge was built across the Mississippi River in Thebes instead of Cairo, it redirected traffic away. Other new bridges over the years have also meant that Cairo was bypassed for other cities. Even Cairo’s own Mississippi River & Ohio River bridges hurt the town, because it ended the ferry industry that had thrived in Cairo.

All of this loss of industry meant a loss of income, tax revenue, and jobs. By the time of the 2020 census, the population in Cairo had gone down 89% from its peak steamboat years. Today, there is a lack of grocery stores, gas stations, medical facilities, and housing in Cairo- besides the lack of jobs. In 2022, HUD closed an affordable housing high rise in town, displacing many residents who have nowhere else to go in town. This isn’t the first affordable housing project that HUD has closed in Cairo, but it has not rebuilt and added any new ones either.

Floods in Cairo

Cairo is a city on the confluence of two rivers, so of course flooding is a concern. In 1937 there was a devastating flood that destroyed much of town. In 2011, once again Cairo faced the possibility of catastrophic flooding. The Mississippi had surged, which caused the Ohio to also rise. Cairo’s levee was holding back the flood, but barely. There were leaks and cracks and it didn’t look good. The town was told to evacuate, and some did- but of course there were holdouts. The Army Corps of Engineers had prepared for this possibility, so there was hope, right? Well, maybe. The plan that had been in place for decades involved a floodway in Missouri across the river. A floodway is a piece of land that the Corps could flood to relieve the pressure on Cairo. To do this, they would blow up the floodway levee, which would flood the land there, and presumably save Cairo. The problem was that the Army Corps was hesitating on actually activating the floodway.

When it was created, the government paid landowners for the right to flood their property. But over time, this pocket of land became good farmland, the farmers didn’t want to give that up. When it became apparent that the floodway needed to be activated, the farmers began protesting that their farmland was more valuable than the city of Cairo. They bugged their Congressmen, who wrote to Obama to try to get him to stop the Army Corps from blowing up the floodway levee. The Missouri Attorney General filed a lawsuit to try to stop the floodway activation.

Most egregious of all, and still bitterly remembered by Cairo residents, Missouri House Speaker Steve Tilley advocated for letting Cairo flood instead of the farmland. When asked about the situation and which he would rather have flooded, Tilley publicly told reporters, “Cairo. I’ve been there. Trust me. Cairo.” and later reiterated “Have you been to Cairo? OK, then you know what I’m saying then.” Over a decade later, when visiting Cairo we heard this quote from residents who are still pissed about it. Eventually, after hemming and hawing, the Army Corps did detonate the levee to activate the floodway, but not until millions of dollars of damage had been done to Cairo and other nearby communities in Alexander County.

So, what really happened to Cairo?

It’s impossible to pinpoint which of these factors was the nail in the coffin. Maybe Cairo could have recovered from race riots like other cities did, but how does a town recover when so many prominent business owners would rather ruin their own business instead of integrate? Maybe Cairo could have adapted and found new industry when river trades declined, but what do you do when there’s no support from the state or federal government? It’s one thing to try to recover from flood damage, but can a town recover from a general attitude that they don’t matter? Can you recover from politicians saying farmland is more important than the homes of your residents? I don’t think anyone can really answer this question, Cairo has had such a unique history and it’s impossible to isolate just part of it.

Our Thoughts on Cairo, IL

We’ve been thinking and talking a lot about Cairo since our visit. On our travels we’ve driven through a lot of dying small towns, but none as bad as Cairo. But it’s so hard to know what a town like that needs. If you bring in big new businesses, will it lead to gentrification and pushing out the original residents? Usually this kind of gentrification and influx of business benefits mostly white people, which would be like history repeating itself again. Or does it just need a totally fresh start as a new town? But what makes a town? Is it the buildings? The name? Or is it the people? And if a town becomes populated with all new people, is it the same town?

Our guide Tara told us her work to preserve her hometown is guided by her faith. She believes that maybe Cairo had to go through these hardships so the slate could be wiped clean and the city can be reborn. There’s still a lot of work to be done to save Cairo, but the first step is finding people who care enough to do the work

If we visit Cairo again in a year, some of the buildings we saw might not be there anymore. But the people will be there and the history will be there and the spirit of those trying their hardest to make a difference in the community will be there. TCHPP sums it up well on their website, “In reality, our cherished little town as we remember it only exists in two places: in our hearts and with the individuals who maintain the artifacts and tangible history of Cairo.”