The NIKE missile program was launched in the 1950s as a highly visible symbol of America’s strength and defense readiness. It was the first nationwide air defense system, developed in response to growing Cold War tensions. Fears of a Soviet nuclear attack led the U.S. Army to begin planning a national surface-to-air missile defense system in 1951. By 1953, the Army had selected boards responsible for acquiring land and constructing the sites, while Douglas Aircraft Company and Bell Laboratories began producing missiles and other essential equipment. The program was named NIKE after the Greek goddess of victory. These Cold War relics are among the many abandoned places in Virginia that offer a glimpse into a tense period in American history.

Fairfax County, Virginia was once home to three NIKE missile sites. Each site consisted of a missile launcher and an integrated control area, usually about 1-3 miles apart from each other. The Fairfax County sites were strategically chosen to form a ring of defense around Washington DC. The power of the 3 sites was strong enough to (theoretically) protect DC out to the Atlantic Ocean.

Great Falls NIKE Missile Sites

While camping at Lake Fairfax Park in Reston, we visited the two pieces of the Great Falls/Herndon NIKE missile site. Our adventure began at Great Falls Nike Park, which is tucked near an elementary school. Reaching the park required driving through the school’s lot, and we narrowly avoided school pick-up time. We were able to leave during pick-up since we were going against the flow of traffic, but if we had arrived just a little later, we would have been stuck behind a long line of waiting parents.

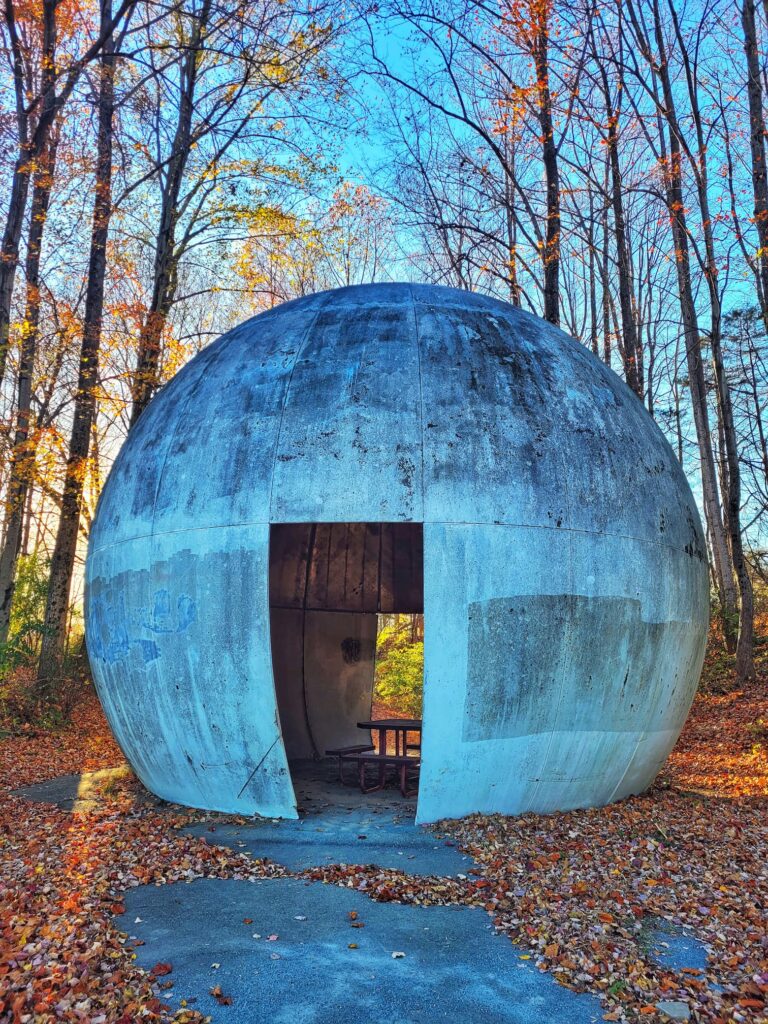

The Great Falls site was built in 1954 and activated in 1955. When it was decommissioned in 1962, all weapons and valuable materials were removed, leaving the buildings to deteriorate. In the early 1980s, the County Park Authority took over and repurposed the site into a park. Today, a tennis court and baseball fields sit atop the buried missile magazine hatches. The only visible remnants include some old barbed wire fencing, an earth berm where missiles were once fueled, and the most intriguing feature: an Air Force radar dome. This gap-filler radar dome would have detected low-flying enemy aircraft that long-range radar systems might have missed. Interestingly, this dome would not have been at a launch site; it likely came from the nearby Integrated Fire Control Site, but no one seems to know when or why it was moved here. Aside from the park’s name, there is no signage explaining the site’s history or the radar dome’s purpose, so if you’re not actively researching the places you visit, you could easily miss some fascinating history.

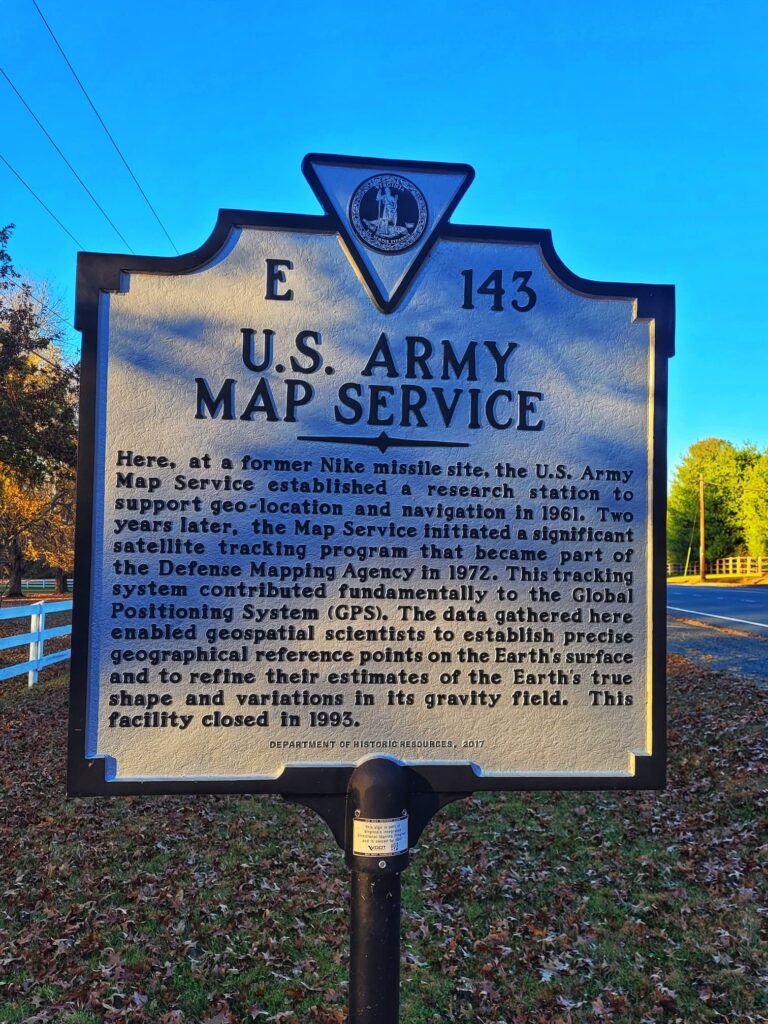

Next, we headed to Turner Farm Park, which was acquired through eminent domain from local dairy farmer Mark Turner to serve as the Integrated Fire Control Site for the Great Falls launch site. The land was purchased in 1954, and the site was activated in 1955. For government work, they moved surprisingly fast. Originally, the site housed barracks, a mess hall, offices, and two radar towers. When operations ceased in 1962, it became a research station for the U.S. Army Map Service, where geolocation and navigation work contributed to the development of GPS.

The mapping facility closed in 1993, and in 1999, the land was transferred to the Park Authority. Since then, Turner Farm has operated as an observatory park. Most of the original NIKE structures have been demolished, but the southern radar tower remains, having been converted into an observatory by the Army. Today, the park offers weekly public astronomy programs.

We didn’t make it out to one of the astronomy programs, but we were excited to still visit and check out the site. Until we got there and realized the observatory is inside a large locked fenced area. We knew we couldn’t go in the building, but we thought we’d still be able to get a closer look. There are even paths and benches around the building that were locked up, which was really strange.

So after a quick peek there, we walked across the street and down a few hundred feet to the two historic markers here. One is about the Great Falls NIKE site and the other is about the site’s importance in the development of GPS.

Lorton NIKE Missile Site

While some land was acquired through eminent domain, the Army prioritized using government-owned land whenever possible. This led to the largest of the Fairfax County NIKE sites, Lorton. The Army obtained 30 acres from the D.C. Department of Corrections’ Lorton Prison complex. Because this site was significantly larger than a standard NIKE installation, it was built as a double site with six magazines instead of the usual three and twice the standard staff.

Construction at Lorton began in 1954, and by 1955, it was ready for the public unveiling of the NIKE program. Its size and proximity to D.C. earned it the title of the “National NIKE Site.” In its early days, it hosted foreign dignitaries, politicians, and public open houses.

Lorton was farther from where we stayed in Fairfax County, but after doing more research, I wish we had visited. The site is now owned by the Park Authority, but it hasn’t been developed. There have been discussions about establishing a Cold War Museum, but no concrete plans exist. Large slabs of concrete cover the missile staging areas, and according to park staff, they don’t even know exactly what lies beneath since everything was welded shut and has never been opened. There’s also a historic marker nearby, making it an interesting stop for those exploring abandoned places in Virginia.

Pope’s Head NIKE Missile Site

The third Fairfax County NIKE site is Pope’s Head Park in Fairfax Station. Like Great Falls, it was an Ajax missile site. We didn’t visit, but based on online research, it appears there’s little to no evidence remaining. A historic marker in front of a nearby police station commemorates the site’s history.

The End of an Era for the NIKE Project

When Eisenhower took office, his “New Look” policy aimed to reduce foreign policy costs by replacing the NIKE-Ajax missile with the NIKE-Hercules. The Hercules missiles had nuclear warheads capable of destroying multiple attackers with a single missile at a lower cost than the Ajax. They could reach altitudes of 100,000 feet at speeds of Mach 3.5 and had twice the range of the Ajax.

The Hercules missiles were designed to fit into existing Ajax launchers with minimal modifications. By this time, over 3,000 NIKE-Ajax launchers existed at almost 300 sites nationwide. Lorton served as the prototype site for the Hercules conversion, but ultimately, only about one-third of NIKE sites were upgraded. The Great Falls and Fairfax sites remained Ajax-only installations.

The introduction of nuclear-capable Hercules missiles led to increased security measures, including new alarms, fences, and guardhouses. Military police detachments took over security, and public open houses were discontinued.

Despite its intended cost savings, the Hercules transition was expensive. To offset costs, the Army transferred many Ajax sites to the National Guard. In Fairfax County, the National Guard took over the Fairfax site and the Ajax portion of Lorton in 1958. By 1960, the Army began closing Ajax sites due to rising operational costs. The Great Falls site closed in 1961, the Fairfax site followed in 1963, and the Lorton National Site remained operational until 1973. The last NIKE battery was decommissioned in Texas in 1983.

NIKE Missile Sites Across the Country

The story of the Fairfax County NIKE missile sites isn’t all that unusual. Across the country you’ll find Nike Missile Parks (literally, there’s so many called that). Some have been razed to the ground with parks built on tops, others have structures remaining, and still others have markers and monuments commemorating the history. While some sites have been repurposed, others remain as eerie reminders of history, making them intriguing destinations for those interested in abandoned places and Cold War history. There are over close to 300 NIKE sites, so I don’t think I’ll be able to visit them all, but I definitely want to make a point to visit more as we travel. Next up on my bucket list is Nike Park in Addison, IL which still has a tower you can climb.